Riviera Beach

Riviera BeachFair, 67°

Wind: 9.2 mph, S

Riviera Beach

Riviera Beach

A century ago, a movie ticket was just a quarter. To get to the theater, an automobile could fill up for just 14 cents a gallon. Bob Barker, Joseph Heller and Millersville resident Rose Merlaine “Mikki” Bowman Carpenter were newborns. The Severn School, established in 1914, hadn’t even graduated its first senior class.

During her 100 trips around the sun, Mikki has seen more history unfold than many students have even heard about.

Mikki graduated from a Seattle high school in 1940, two years after the start of World War II. She worked a few jobs and learned how to keypunch, which led to a job with Boeing Aircraft. But she wanted to do more for the war effort. The money was good, but the hours were long. Shortly after turning 21, she enrolled in the U.S. Navy WAVE program (Women Accepted for Voluntary Emergency Service).

“I felt really bad for all of the men dying in the war, and I felt I should be doing more,” Mikki said. “I just didn’t think it was fair not to be doing my part.”

She and a trainload of female Navy recruits traveled from Seattle to Brooklyn for six weeks of boot camp. Mikki remembered those 3,900 miles in a train car fondly. Happy to begin service to her country, Mikki even found boot camp in Brooklyn enjoyable.

“We marched every place we went, singing songs,” Mikki said.

Early in her military career, Mikki was supposed to be on duty early on a Sunday morning, but she had planned to attend church. Because of church, Mikki was five minutes late for her Navy obligation.

“I remember that I said, ‘My God means more to me than anything on earth — the Navy or anything else,’” Mikki said. “I think they were ready to court martial me, but when they saw that I was that sincere and not frivolous about it, they said it was OK, but not to do it again.”

After boot camp, Mikki was asked where she wanted to be stationed. She told them where she didn’t want to reside.

“Anywhere but Washington, D.C., and that’s exactly where they sent me,” Mikki said.

When asked what she wanted to do, she said she wanted to be a corpsman so she could take care of the men coming back from war. Once the Navy found out she had keypunch experience, she was assigned as a communications technician, where she ultimately earned a promotion.

Mikki recalled that she was required to wear her uniform anytime she was in public, and she proudly complied.

“I think it was very important for all of us women to show we supported the war,” Mikki said. “We didn’t fight, but we did everything we could to support those who did. I was proud of that.”

Although not her first choice of assignment, a communications technician was involved in breaking down Japanese codes, which was important in winning the war. And it was then that she met Bill Carpenter, a chief petty officer in the Navy also working in code-breaking, who had been stationed in Hawaii after the Pearl Harbor attack. The couple married in 1946, which was also the year Mikki retired from the Navy to start a family.

They lived in Alexandria, Virginia, until the family was sent to Guam for a year. Next, they lived in Japan for three years and then Germany for three years. In 1966, the family returned stateside and settled in Glen Burnie. After retiring from the military, both Carpenters worked at the National Security Agency.

During Mikki’s tenure with the Navy and NSA, her work as a cryptologist included Japanese and Russian code breaking. Mikki didn’t find her work particularly interesting, or for that matter valuable, but history will argue that code breaking and all of those involved played a pivotal role in ending the war.

“I think of all those who died and those who came back with difficulties,” Mikki said. “I didn’t do anything; it makes me feel bad. I am so glad I was in the war. I’m very glad I was in it.”

After retiring from the NSA, the Carpenters spent time in West Virginia, Florida, and they even spent time traveling the U.S. in a recreational vehicle. Bill passed away in 2001, and Mikki returned to Anne Arundel County. In addition to volunteering throughout her community, she was a member of the garden ministry at Our Lady of the Fields Catholic Church in Millersville, where she was responsible for keeping the property picturesque.

“Mom has always lived a life of service, whether it be helping friends and neighbors or volunteering at Our Lady of the Fields, Meals on Wheels and Partners in Care, driving people to appointments who were much younger than she was,” said her son, Bill Carpenter.

Mikki is enshrined in the Military Women’s Memorial at Arlington National Cemetery.

Several family members recently visited the memorial, where an administrator spoke with Mikki and thanked her for paving the way for women serving in the armed forces.

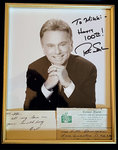

She may not see herself as important to the war effort or see significance in hitting the 100 mark, but some celebrities feel otherwise. “Wheel of Fortune” host Pat Sajak sent Mikki a signed photo and card congratulating her on her golden birthday, as did CBS journalist and anchor Scott Pelley. Mikki played golf with Pelley’s mother when the Carpenters lived in Florida. When she voted last fall, a television news camera crew interviewed her, and she told them she first voted for Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) in 1944.

Mikki was active in her Brightwood neighborhood until recently, including volunteering for community events, especially those for children. In 2018, she was a cofounder of B.R.A.Ts. — Brightwood Retirees Active Tuesdays. Earlier this year, neighbor Jan Jones created a picture book to celebrate Mikki and another soon-to-be centenarian.

“Mikki is such a valuable member of Brightwood,” Jones said. “The book is for everyone to reflect back and enjoy Brightwood’s golden girls. One-hundred is a real milestone, and we want to celebrate it.”

1 comment on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here

Carpenter

Our Mom, our hero!

Friday, March 17, 2023 Report this